Written by: Anita Raj, Amy Vatne Bintliff, and Wendy Wei Cheung of UCSD Center on Gender Equity and Health

In the last year, physical violence against women[1] in California doubled, according to a new survey conducted by our Center on Gender Equity and Health at the University of California San Diego. As a response, this year, the California governor has the opportunity to approve the state legislature budget that increases violence prevention funding, including $15 million to prevent domestic and sexual violence. In order to successfully prevent violence before it takes place at all , we need to secure a long-term commitment to expanded prevention programs in communities throughout the state.

California San Diego. As a response, this year, the California governor has the opportunity to approve the state legislature budget that increases violence prevention funding, including $15 million to prevent domestic and sexual violence. In order to successfully prevent violence before it takes place at all , we need to secure a long-term commitment to expanded prevention programs in communities throughout the state.

Given that this violence often starts in adolescence, schools must be part of our efforts to prevent violence. Equipping our schools with the knowledge and resources to engage in successful prevention efforts will strengthen our ability to create healthy and safe communities free from violence in California.

What do we know?

Media and advocacy movements focus much attention on violence in schools in the form of mass shootings, but little on the ongoing, and far more pervasive, interpersonal violence occurring at schools. National data from U.S. high school students in 2019 indicate that 8% have been in a physical fight on school property and 3% have carried a weapon to school, with boys more likely than girls to report these concerns. This is likely the tip of the iceberg and inadequately reflects on forms of violence more commonly experienced by girls, such as sexual harassment.

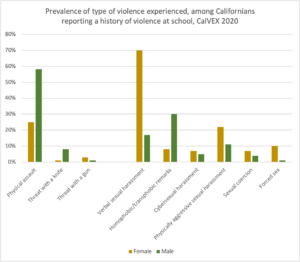

Our analysis of CalVEX 2020 survey data was taken from a representative sample of more than 2000 Californians in March 2020, at the start of the pandemic. These data reveal that both physical and sexual violence occur in our schools, and with sharp gender differences. One in five (21%) California adults have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at school, with 18% of cisgender females and 24% of cisgender males reporting this. Among those reporting school-based violence, the forms of violence were diverse and differed by gender. (See Graph 1.) Participants who self-identified as male reported physical assault and homophobic/transphobic remarks as their most common forms of abuse, where females reported verbal sexual harassment and physically aggressive sexual harassment (e.g., groping, stalking) as the most common forms of abuse experienced. Shockingly, one in 10 females who reported violence at school experienced it in the form of forced sex. These findings are deeply disturbing, and speak to inadequate protection in our schools and potentially the questionable school climate that may tolerate such abuses.

What can be done?

The California’s Department of Education offers guidance toward policy and practical prevention of violence and other abuses at school, and their includes violence prevention education for students, including education that focuses on partner and sexual violence as well as sex trafficking. However, too often, school officials are ill-prepared to focus on these topics or unaware of their pervasiveness and the need to prioritize this type of education for adolescent populations. To that end, we offer the following key recommendations for schools:

- Recognize verbal abuse, as well as physical and sexual abuses, as harmful to youth, all the more so if they contain overt or subtle threats physical or sexual assault. Schools must consider the range and experiences of violence and abuse; the alternative is tolerance of violence.

- Support those who come forward with allegations of abuse or mistreatment. Too often, we see under-reporting and correspondingly normalization of abuse and victim blaming .

- Ensure accountability structures are in place to address violence, in ways that support positive mental health and social-emotional learning, as opposed to punitive practices and policing. Healing and restorative justice opportunities hold greater value than punishment or separation of students in some cases .

- Maintain gender -disaggregated data on reported experiences and monitor state-level data on prevalence of these abuses, including gender non-binary students in data disaggregation efforts. Tracking escalations of violence or disclosure of violence in schools statewide can inform gender-responsive programming.

- Consider the use of evidence-based prevention programming that affects school climate and culture. Programming should center the intersectionality of student identities in order to alter social norms accepting of violence and gender norms reinforcing male abuse against females and LGBTQI+ individuals.

- Mandate professional development that provides educators with the tools and skills to appropriately intervene in violent situations. Trainings, such as bystander interventions, must be adapted to the school environment and adhere to established protocols.

- Above and beyond holistic, school-wide prevention programs, provide funding for additional counselors and student support staff in schools so that educational programming can be delivered by those who have been trained in trauma-informed practices. Survivors of school violence and harassment need supportive programming and those who offend need high-quality, research-based instruction to prevent repeated offenses. Too often, perpetrators receive arbitrary consequences that lack in-depth education components

Violence against and harassment of adolescents has too long been viewed as a rite of passage in our schools. The COVID-19 pandemic has cost us much, particularly in terms of education and risk for violence, but it may provide opportunity – given the timely increase in prevention funding from the state – to address the persistent interpersonal violence occurring in our schools. Further, we can tackle the gendered nature of this violence at an earlier age and disrupt the cycle of violence that occurs across a person’s lifetime.

*This analysis focuses on cis-gender individuals, as the number of transgender individuals in the study was too small in number for accurate analysis. There is need to focus specifically on transgender individuals, as violence may have increased for this population as well.